Per leggere questo articolo in italiano, clicca qui.

Originated in the area at south and east of the Himalayas, tea has traveled around the world, and created, in each place, different traditions, ceremonies and habits in its production and in its consumption. Today, since tea is produced mainly in Asia and Africa and consumed all over the world, it can be considered an example of “cross-cultural consumption”.

Despite the current tendencies toward food nationalization, we need to remember that food has been traveling for as long as human populations have done. In fact, there’s evidence that the first movements of humans are associated with movements of food products [1]. In modern food systems, however, the movement of food does not necessarily follow the movement of peoples. In fact, consumers around the world have access to industrially produced foods that are assembled in distant locations (as discussed in the previous article on industrial food, here).

Which discourses, narrations and meanings do we associate to food and drink coming from places beyond our borders? For instance, if we go eat sushi, or buy American snacks, we might be doing it because we are attracted by foreign tastes, or to feel closer to a “far-away land”. In this case we consciously associate these products to their origin. Meanwhile, we might be eating food produced, processed and packaged in three different countries, and claim them as our own. Coffee, for instance, is produced mainly in South America and Asia, but is advertised in Italy as “the real Italian espresso”. Or, tea, for the British, is so ingrained in most people’s daily habits that its origin is easily forgotten or disregarded.

To make sense of the way food travels across spaces and cultures, two opposing and contrasting paradigms have been suggested in anthropology. The first sees (mass) consumption as a homogenizing force that overcomes local cultures (homogenization paradigm); the other suggests that consumers, with creativity, re-contextualize products, building new uses and meanings in their socio-cultural context (creolization paradigm)[2].

The homogenization paradigm aims to explain how Western products have spread in the non-Western world, supplanting local traditions [3] . Terms such as Coca-colonization and McDonaldization have been created to underline the impact that global products and chains have in non-Western regions, such as supplanting local products and production processes. From the studies supporting this paradigm, we can value the implicit critique to the imbalances between Western powers and large companies on one side, and non-Western countries on the other. However, these studies fail to recognize the agency of the consumers in non-western countries. In fact, ethnographic evidences suggest a more complex situation than passive homogenization[4]. Consumption, the act of buying and using a commodity, is not a passive process.

In fact, when consuming a good, the good is re-appropriated and re-inserted into the socio-cultural context of each consumer [7]. In other words, the consumption of goods and food is a creative process. Therefore, when a product coming from abroad enters a new context, it enters a specific historical moment and a specific cultural context [8] , which shapes the uses and meanings attributed to it.

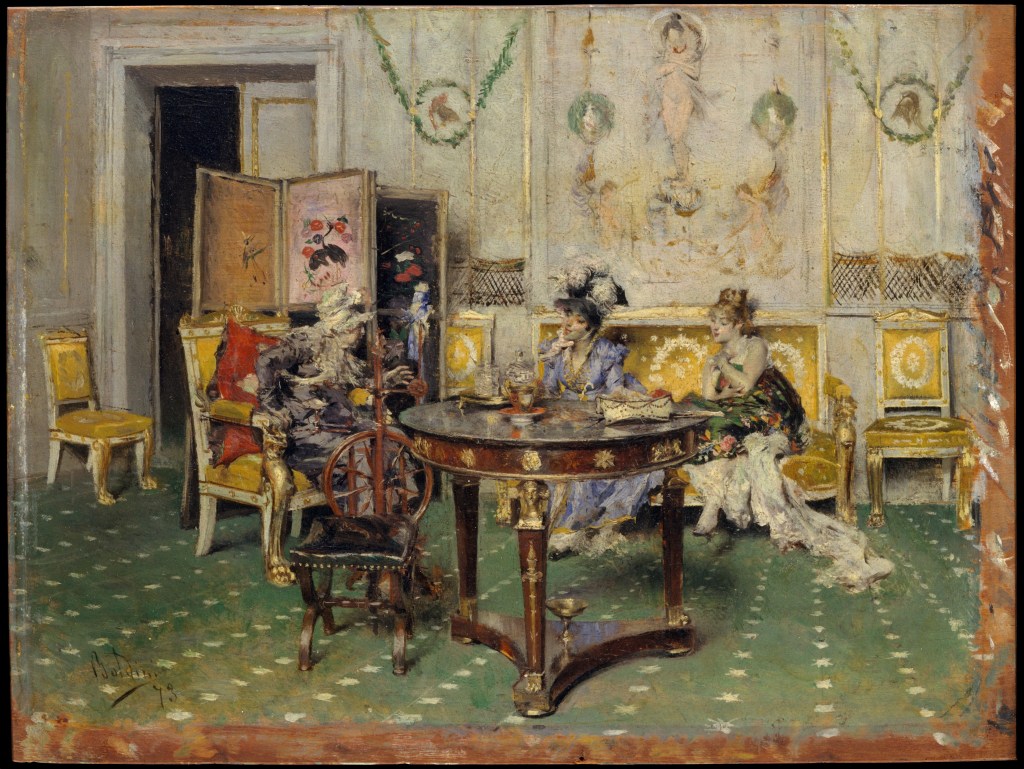

In an ethnography on McDonald’s in Beijing [9] , the anthropologist Yunxiang Yan showed a contrast between the way the space had been designed beforehand, and how it was actually used by consumers. The primary objective of the fast-food chain, in fact, was to create a space designed for quick meals. Instead, Beijing customers went to McDonald’s for long family events or, in the case of very young people, for romantic dates. This is one of many examples that demonstrate that the intention of companies or producers of “global” goods does not necessarily correspond to the intentions and uses of customers and consumers. The limit of the homogenization paradigm is assuming that when commodities enter a new culture, they keep and communicate the producers’ values, which are passively accepted by the consumers. The homogenization paradigm does not consider the creativity of the consumers, who relate to commodities in different and contradictory ways [10]. The locations where global commodities (including food) enter are not blank canvases, but have specific historical, social and cultural contexts. In the words of anthropologist Mintz: “when unfamiliar substances are taken up by new users, they enter into pre-existing social and psychological contexts and acquire – or are given – contextual meanings by those who use them” [11].

To express this complexity of intercultural consumption, the paradigm of creolization or hybridization has been suggested [12] . This paradigm sees consumption as a contextual and creative process. This analysis of consumption allows us to understand not only the integration of Western goods in non-Western locations, but also the entry of non-Western goods into the West [13] , as in the case of tea. Teas, especially those defined as artisanal and are drunk by tea aficionados, are not a “global” commodity like McDonalds and Coca-Cola, but are highly localized products [14].

Yet, the paradigm of creolization also has its limits. In particular, it tends to consider the culture of origin and the culture of arrival of the products as two pure entities that will “meet” only in consumption. However, cultures, social contexts and history are not fixed entities, but are subject to external stimuli and are in communication with each other. To give an example, I would think of how consumer demand for a particular product leads to changes in production. This was the case, when, in the 19th century, the Japanese government invested (with little success) in the production of black tea, because that was the most popular type of tea in Europe [15].

I am now addressing tea enthusiasts in particular. How important is it to you, if it is at all, where the tea you drink comes from? Can one of these paradigms represent your way of consuming tea? Or do you think the issue is more complex and none of these paradigms are enough? If you’d like, tell me your opinion in the comments, I am very curious to know what you think! 😊

[1] Jones et al 2011

[2] Cook e Crang 1996; Howes 1996

[3] Jackson 1999, Howes 1996

[4] Howes 1996; Classen 1996; James 1996; Weiss 1996; Hendrickson 1996; Yan 2000

[5] Kopytoff 1986

[6] Appadurai 1986

[7] Miller 1987, 1998

[8] Classen 1996

[9] Yan 2000

[10] Howes, 1996; Jackson 1999

[11] Mintz 1985: 6

[12]Howes 1996

[13] Hendrickson 1996

[14] see for example Zhang 2014 sul tè Pu’er; Kajima et al. 2017 sui tè giapponesi; Besky 2014 sul tè Darjeeling

[15] Farris 2019

Bibliography

- Appadurai, A. (1986) ‘Introduction: Commodities and the politics of Value’. In Appadurai, A. The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, pp. 3-63.

- Besky, S. (2014). ‘The Labor of Terroir and the Terroir of Labor: Geographical Indication and Darjeeling Tea Plantations’, Agriculture and Human Values, Vol. 31: 83-96.

- Classen, C. (1996) ‘Sugar Cane, Coca-Cola and Hypermarkets: Consumption and Surrealism in the Argentine Northwest’. In: Howes, D. Cross-Cultural Consumption: Global Markets, Local Realities. Oxon: Routledge, pp.39-54. [9] Yan 2000

- Cook, I. and Crang, P. (1996). ‘The World on a Plate: Culinary Culture, Displacement and Geographical Knowledges’, Journal of Material Culture, Vol. 1(2), pp. 131-153. Howes 1996

- Farris, W.W. (2019). A Bowl for a Coin: a Commodity History of Japanese Tea. Honolulu: University of Hawai’I Press.

- Hendrickson, C. (1996) ‘Selling Guatemala: Maya Export Products in US Mail-Order Catalogues’. In: Howes, D. Cross-Cultural Consumption: Global Markets, Local Realities. Oxon: Routledge, pp. 106-121.

- Howes, D. (1996) ‘Introduction: Commodities and Cultural Borders’. In: Howes, D. Cross-Cultural Consumption: Global Markets, Local Realities. Oxon: Routledge, pp. 1-16.

- Jackson, P. (1999). ‘The Traffic in Things’, Transaction of the Institute of British Geographers, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 95-108.

- James, A. (1996) ‘Cooking the Books: Global or Local Identities in Contemporary British Food Cultures?’ In: Howes, D. Cross-Cultural Consumption: Global Markets, Local Realities. Oxon: Routledge, pp. 77-92. Weiss 1996;

- Jones, M., Hunt, H., Lightfoot, E., Lister, D., Liu X. and Motuzaite-Matuzeviciute, G. (2011) ‘Food globalization in prehistory’, World Archaeology, Vol. 43, No. 4, pp. 665-675

- Kajima, S., Tanaka, Y., Uchiyama, Y., (2017) ‘Japanese Sake And Tea As Place-based Products: A Comparison of Regional Certifications of Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems, Geopark, Biosphere Reserves, and Geographical Indication at Product Level Certification’, Journal of Ethnic Food, Vol. 4, pp. 80-87.

- Kopitoff, I. (1986) ‘The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process”. In Appadurai, A. The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, pp. 64-91

- Miller, D. (1987) ‘Introduction’. In: MIller, D., Material Culture and Mass Consumption. Oxford: Basil Blackwell Inc., pp. 3-18

- Miller, D. (1998). ‘Introduction’. In: A Theory of Shopping. Cambridge: Polity Press, pp. 1-13.

- Mintz, S.W. (1985). Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. New York: Penguin Books.

- Yan, Yunxiang (2000) ‘Of hamburger and social space: consuming McDonald’s in Beijing’. In: Davis, D.S. The Consumer Revolution in Urban China. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 201-225.

- Zhang, J. (2014) Puer Tea: Ancient Caravans and Urban Chic. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Featured image created using Artificial Intelligence.

Lascia un commento