Per leggere questo articolo in italiano, clicca qui.

Tea consumption in Japan has ancient roots and precedes the very existence of Japan: many centuries have passed between the time the first tea arrived on the Japanese islands from China to the time when Japan became a nation-state.

It seems that the first tea was drunk in Japan during the Nara period (710-784), when Emperor Shomu received a gift of tea from the Chinese Tang court, which was served to a crowd of one hundred monks who had visited the then capital Nara [1] . However, it was not until the Heian period (794-1185) that tea was planted [2]. The first to import Camellia sinensis seeds into the Japanese islands are said to be two Buddhist monks who, in the same year (804), embarked for China in order to study Buddhism: Seicho and the younger Kukai. The two, once back home, gave rise to two Buddhist schools, Tendai and Shingon respectively [3] . Shortly after, in 814, the elderly monk Eichu brought back tea from China. Tea at this time was carried in the form of dancha, consisting of fermented tea bricks. It is said that when he served tea to the emperor visiting his temple, the ruler liked the drink so much that he established its cultivation near Kyoto. The cultivated tea was available exclusively to the imperial court and its medical practicioners, and for imperial and monastic ceremonies . [4]

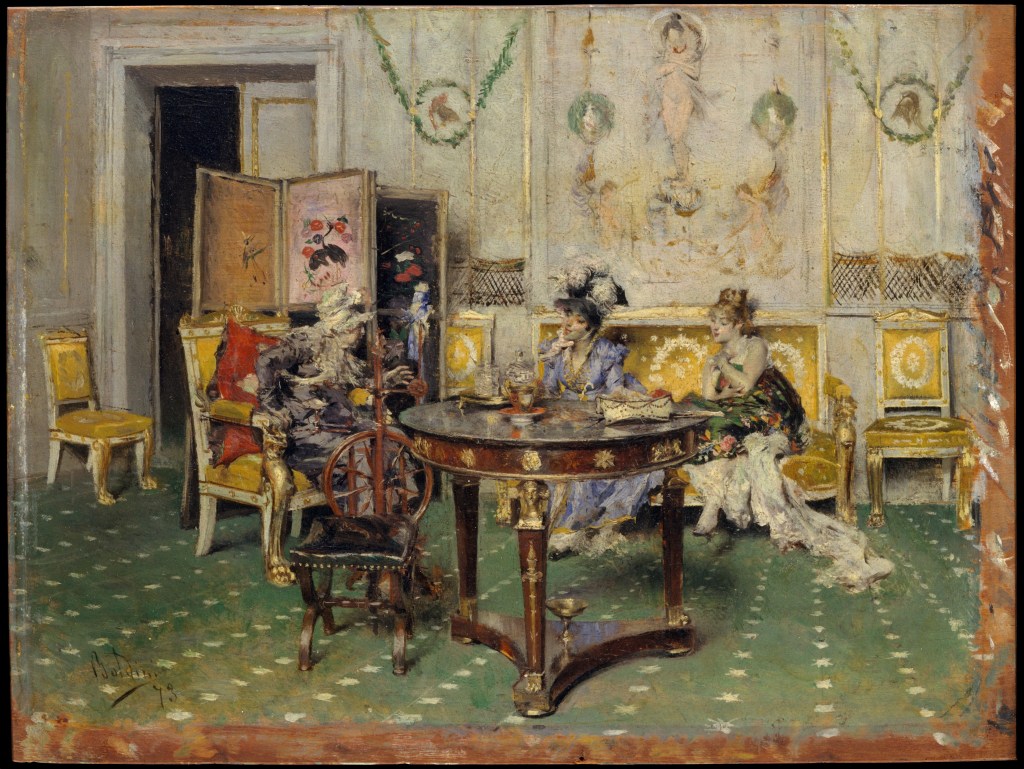

We have to wait until the 12th century for powdered tea (matcha) to be drunk on the Japanese islands. Tradition says that the monk Eisai, also returning from several trips to China, brought Zen Buddhism to Japan, and, together with this, matcha [5] . For many centuries, this will be the canonical tea produced and drunk on the Japanese islands. In fact, matcha is the tea of the traditional tea ceremony, called Chado, meaning “way of tea”.

The spread of powdered tea in the Japanese islands is closely linked to the spread of the Zen Buddhist school. Matcha, in fact, was appreciated by the monks because it was helpful during meditation: it kept the meditating monk awake, and, at the same time, calmed them down [6]. Eisai himself, in a medical writing on the benefits of tea, asserted that in addition to keeping one awake during Zen meditation, tea promoted harmony in the entire body [7] .

It is no coincidence, in fact, that the Japanese myth about the origin of tea is linked to the practice of meditation. The main character of this story is Bodhidharma (also known as Daruma), a wandering monk who, according to hagiographies, travelled from India to southern China in the 5th century [8] . Daruma is considered the founder of Zen Buddhism. Japanese legend has it that, because he kept falling asleep, Daruma was unable to meditate. To overcome the problem, he cut off his eyelids and threw them away; from these, it is said, the tea plant sprouted.

Throughout its journey across historical eras, in a more or less ritualized way, the consumption of matcha tea in the tea ceremony has been linked to the pinnacle of power that controlled what would later become the Japanese state. The anthropologist Kristin Surak writes about this and on the role that the tea ceremony has today in her monograph “ Making Tea Making Japan: Cultural Nationalism in Practice ”.

[1] Van Driem, G.L. (2019). The Tale of Tea: A Comprehensive History of Tea from Prehistoric Times to the Present Day. Leiden; Boston: Brill.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

Scrivi una risposta a Tra Zen e leggenda: l’arrivo del tè in Giappone – One Purple Magpie Cancella risposta